January 6th failed because ubiquitous technical surveillance is making us stupid.

EXIT is a fraternity dedicated to shorting managerial systems and building the human institutions that come next. Learn more here:

[None of what follows should be construed as a lack of sympathy for the railroading of the J6 detainees: this is strictly an attempt to derive principles from what happened, with the benefit of five years’ hindsight.]

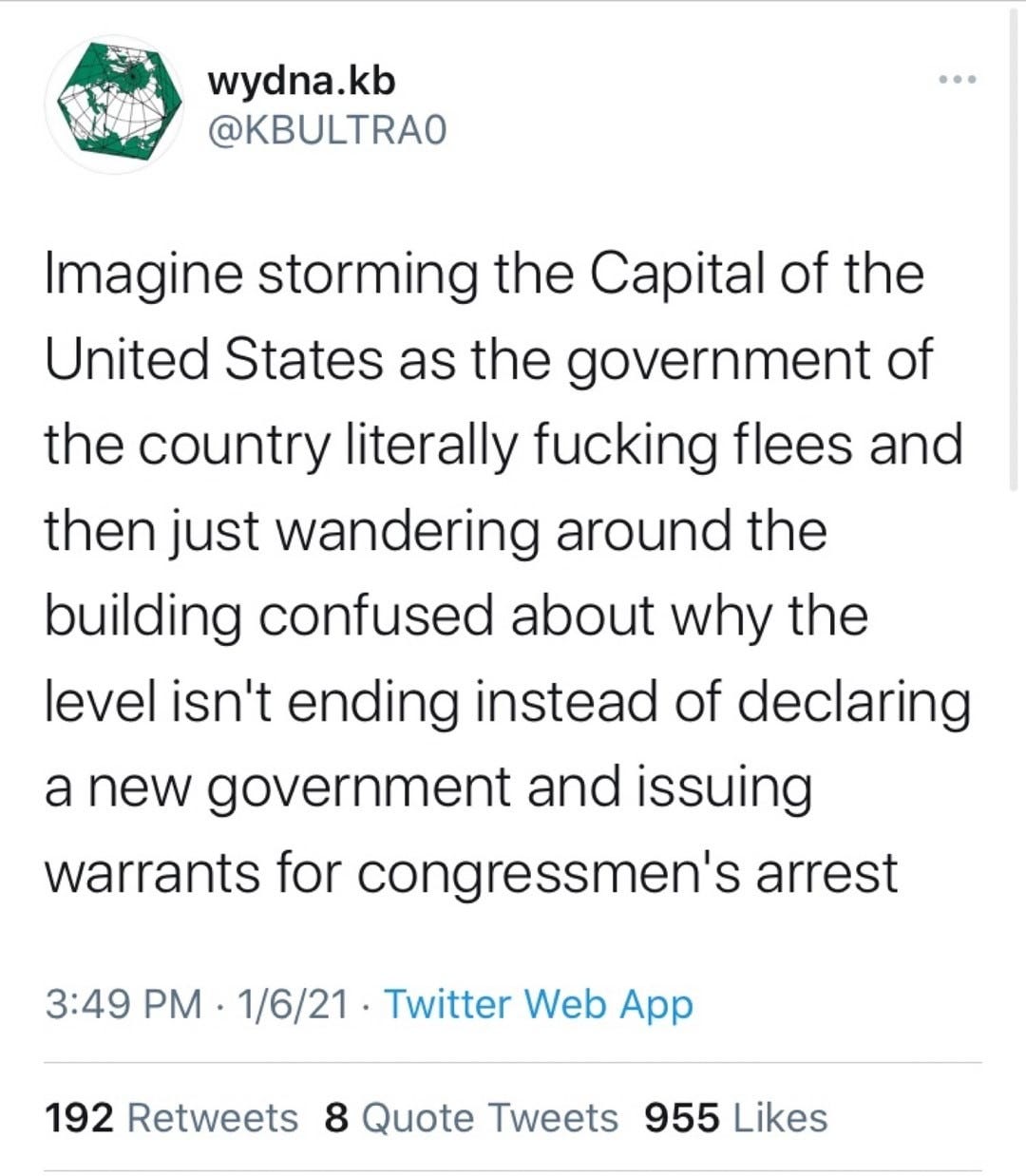

On the fifth anniversary of January 6th, this tweet is worth some study and meditation.

Right-wingers tend to moralize: they like to think about success and failure in terms of personal responsibility and moral courage. This is good for some domains of personal development, but it can lead into cul-de-sacs where you settle for simple and unhelpful answers.

The consensus opinion seems to be that January 6th was a clown-show because the organizers were bad people: stupid, or irresponsible, or compromised. In varying degrees this may be true, but it doesn’t actually explain anything, and offers no concrete prescriptions.

I’m going to suggest an alternative theory:

January 6th failed because ubiquitous technical surveillance makes dissidents (including me, including you) stupid.

In the 2010s, Western intelligence services developed very robust systems for infiltrating and monitoring online discourse, originally (ostensibly) to suppress Islamist terrorism.

They didn’t have to knock on too many doors to achieve the desired effect:

Simply by establishing the widespread (and justified) suspicion that any Islamist group chat was likely to be infiltrated by federal agents, they made it extremely difficult for terrorists to recruit and organize online.

The same phenomenon occurred with right-aligned groups in the aftermath of Charlottesville. All it took was a few high-profile roll-ups of right-wing group chats — some of which were explicitly created by intelligence assets for entrapment purposes, and all of which were infiltrated very soon after their creation.

January 6th was a consummation: not only a demonstration of the state’s power to flush out, identify, and punish organized dissent, but a massive flex of its ability to scramble thoughtcrime.

Fed Suspicion doesn’t just suppress organizing — it suppresses many avenues of forecasting and planning.

If you ask anyone who writes for a living, they’ll tell you that writing is the only way to do certain kinds of thinking. You have to get the words on the page so that you can look at them, like dumping puzzle pieces out on the table.

(This is why most successful writers engineer some method of forcing themselves to vomit everything out first, before they do any editing.)

All kinds of macro structures, themes, fine points, and objections do not emerge to the conscious mind until after you’ve stared at the pieces and moved them around in relation to each other on the page.

You get an idea in your head, and you’re sure there’s something there — but often in the process of trying to get it on the page, you realize you haven’t really thought it through at all.

(Poasting is addictive because it provides an endless stream of these manipulations to perform, with instant feedback — and because it’s all on a screen, you can move the pieces around more fluidly than you can in ink.)

But if you do a lot of writing online, you will quickly become conscious of the impulse to self-censor.

You can’t help thinking of how a particular idea might go over with your audience — often it’s just insecurity about whether your idea is stupid.

But, particularly if your mind wanders to the details of anything that might attract government attention, you start to weigh the consequences of the writing itself (instead of thinking carefully about the topic you’re actually trying to write about.)

This is why popular online right-wing writing is so broad, emotive, and imagistic. You are free to be outraged, as long as you are not contemplating action.

(You are allowed to talk about Theory. This is a post about Theory.)

So, the Right Wing Insurrection on January 6th was also broad, emotive, and imagistic.

Many are puzzled at the lack of thought that seems to have gone into the “insurrection” — but it makes perfect sense if you think of January 6th as Tweeting IRL.

They were doing exactly what they had talked about doing online, to the exact extent they had felt comfortable talking about it: essentially, the expression of anger, and the production of scenes and images — photo-ops, and funny, memetic Content like pooping in Nancy Pelosi’s desk.

They had only ever talked about what they would do on the internet, consciously operating under ubiquitous technical surveillance — and because they couldn’t talk about their intentions seriously, they couldn’t really think about them seriously.

So when they overran the Capitol and the US Government fled in panic, they had no idea what to do, except wait around to get arrested.

Who knows if it was engineered this way on purpose — but Fed Suspicion has proved to be a world-historical instrument of thought control.

It works not by changing your mind, but by pruning lines of inquiry: ensuring that all sorts of thoughts — particularly high-resolution, concrete thoughts — never happen at all.

If you can’t write about a topic, even in an intimate setting, you can’t expose your thinking to constructive feedback, identifying lapses of logic or areas where factual ignorance leads you to flawed conclusions.

Even to discuss such topics in a private setting marks you as (at minimum) lacking in judgment. Intelligent people will — for good reason — distance themselves from you immediately. Feds are no longer necessary: the group chats very effectively police themselves.

So you never lay all the pieces out on the table even for yourself, and all your expectations and plans remain fuzzy and inchoate.

And when you can’t think about certain possibilities rigorously, they take on a feeling of unreality, no matter how confident you may be, in the abstract, that they are both a) uncomfortably likely and b) decisive to your family’s future.

And sure enough, that’s exactly what we observe:

Even very bright people, who are otherwise conscientious and forward-looking and serious-minded, think about the national situation (and their personal situation therein) with roughly the same emotional investment and intellectual rigor as professional sports.

They are “dissident” in the sense that they go online to exchange images and fantasies with other people hostile to the government. They say (and probably genuinely believe) that they are up against a ruthless and murderous enemy — but they are incapable of taking the implications of that belief seriously.

They talk (again, in broad, imagistic terms) about what somebody ought to do to their enemies, while making no effort to acquire the ability to do anything to their enemies, personally or collectively.

They talk about the need to Stand and Fight, while making no preparations for a world in which Standing and Fighting is called for.

All of this talk only serves to dig a hole, loudly and continually signaling hostility to The Regime, and waiting for it to come roaring back.

Like January 6th itself, this surrogate activity almost feels engineered to smoke you out — and justify your punishment — while exposing The Regime to no actual material threat whatsoever.

It’s foolish behavior, but these aren’t foolish people:

If you’re smart enough to think about these questions at all, you’re smart enough to know that it is dangerous to talk publicly about anything direct and concrete in the here and now.

Because these are not foolish people, they compartmentalize: they stick to the domains where their ability to forecast and plan is uninhibited, bringing their brains to the version of the future in which everything stays basically normal, where the professional ladders they’re climbing are still relevant.

They still feel the pall of dread hanging over them, but they simply set it aside: they behave and plan as if they will never have to match words to actions, because they (correctly) judge that all of their rumination on that possibility has been fundamentally unserious.

They deal with this anxiety by venting in safe (emotive, imagistic) ways — and through online arguments over “tactics” (which really just amount to regional or class prejudices): do or don’t learn a trade, do or don’t join the military, do or don’t relocate; the city mouse is doomed, the country mouse is doomed.

Of course, there isn’t one right answer — in fact, you need lots of friends pursuing multiple strategies at the same time.

But the reason otherwise smart people have these endless, pointless fights is to deaden that nagging undercurrent of fear — to convince themselves that whatever course they’ve personally drifted into does not require re-evaluation (because they can’t bring themselves to re-evaluate it.)

As things get more volatile, and confrontation looms closer, and the safe paths narrow, we can no longer defer: it’s increasingly obvious that we need to think seriously about topics that we are unable to think seriously about on the internet.

The danger is that, when a day of decision finally arrives, we will respond to it the way we’ve always talked about it: incontinently.

I am not interested in having my own personal January 6th. I do not fantasize about “bleeding out in the snow”: in my fantasies, I win.

So how can we think these things through?

First: stop doing all your thinking on the internet.

If you’ve ever expressed an “urge to fedpoast", you should stop being a woman, get out a spiral notebook, and go ahead and say what’s on your mind.

“The Founding Fathers would have been stacking bodies by now” — would they? Are you sure? What would that look like? Stop telling yourself that you’re just morally inferior to your ancestors, and game out what Righteous Action would look like.

Write up your detailed plan. What would it take to get you from here to there? What are the “red lines” that would trigger all the various forms of decisive action that you are not currently taking? What risks would you incur? What would the consequences be? Would it lead you somewhere you want to go?

When you’re in an unfriendly jurisdiction, it feels good to tell yourself that you’re going to Stand and Fight.

If that’s your plan, you need to ask yourself: what are the odds of (another) political upheaval in which your enemies are in uncontested control of your security environment?

Is there any plausible scenario in which your being present for that upheaval and shouldering those risks nevertheless accomplishes some worthy aim? What is your actual, no-bullshit plan for accomplishing that aim under those circumstances? What is your plan for your family?

If you’re not going to Stand and Fight, are you going to leave the country? At what point? To where? To do what? With whom?

(As an aside: these “stay or go” online arguments are almost always retarded because A) it’s obvious neither party has thought either scenario through beyond its moral/emotional valence, B) people are in different situations that justify different approaches, and C) because it’s obviously mutually beneficial for friends to deploy both strategies at the same time.)

Just as important: what will the consequences of inaction be? At what point will it become infeasible to keep your head down? (If you do this math and conclude that you can keep your head down indefinitely, then bitching about the government is almost certainly counterproductive and stupid, and you should focus on your job.)

You can lock your fedpoast notebook in a safe, or burn it when you’re done — the point is just to get real with yourself about what you are and aren’t going to do, what it would take, and what it would mean.

This is good for all sorts of fantasies, by the way: stop letting them hang in the air, and either operationalize them or put them to bed. It just happens that this category of fantasy is in the way of real shit you need to do, and might get you pointlessly killed.

Second: start building dual-purpose capacity.

Once you’ve written out and exorcised all your Hollywood ideas about going down in a blaze of glory (or whatever), and figured out what you actually believe about the future and your place in it, you can get down to the real work of preparing — and this will almost certainly involve “dual-purpose capacity”.

You can also think of this as deniable capacity: assets that have a legitimate application here and now, and which happen also to be useful in a more complicated future situation.

There are all kinds of practical organizing and capacity-building activities that are not only not illegal, nor even discouraged, but actually incentivized in various ways by the state.

It’s perfectly legal to build a production business with your friends. It’s perfectly legal to get to know your sheriff and city council, and maybe help a few of them get elected. It’s perfectly legal to become an EMT or volunteer first responder, with freedom of movement and comms access in an emergency. It’s perfectly legal to become a guy (or group of guys) who bring people together and help them solve problems.

These are activities that you can talk freely and in detail about — which means you can think about them much more clearly.

And they’re far more effective at increasing your practical sovereignty — the set of things you are able to do, that no one can stop you from doing — than any self-consciously ideological or state-hostile (let alone violent or criminal) activity.

Many on the Right discuss (in the abstract) the need for “mafias”, but in fact it may be more useful to think of our task as analogous to a mob operation “going straight” — laundering resources into uncontroversial, legitimate, real power flows.

Going back over your fedpoast notebook: the scary high-speed fantasy futures you’ve imagined, and your objectives within them, will be necessarily unique, and that should suggest the resources and relationships that you need to cultivate. What will put you in the most powerful position to lead your family and community as systems fail and responsibilities are abdicated?

If political power flowed from the barrel of a gun, your home arsenal would already mean a lot more than it does. Even in places like Lebanon and Afghanistan, political power flows from habits of obedience and perceptions of legitimate authority. You can pick up this kind of power almost literally off the ground by taking on uncontested responsibilities in your community.

If you don’t know what power flows there are to capture around you, the first step is an area study. Get to know the people and institutions around you: see what crowns are lying in the gutter. (An area study can be a group capacity builder in itself. We’ll discuss this on EXIT calls over the next quarter.)

The Founding Fathers would not be stacking bodies right now.

They would almost certainly be baffled at the gulf between our belligerence and our actual preparation for action.

They built wealth, and courted the wealthy. They spent enormous time and resources working the Parliament (as well as various foreign benefactors). They trained in His Majesty’s Army; they used the empire’s guns to secure their property, and they made enthusiastic use of the empire’s global trade network. None of this was a distraction or a compromise of their political objectives — they would not have succeeded without it.

The American colonies had been peopled and governed by political dissenters from the very beginning. They threw off the yoke only after 175 years of carefully building parallel institutions under the watchful eye of the most powerful empire in history to that point — and that empire had nothing on ours in terms of capacity to monitor and eliminate threats.

Given the trajectory of our empire, I don’t think we’ll have to wait that long — but that also means we are running out of time.

Get offline, and create space for yourself to think seriously about the future. The good news is that almost nobody else is doing it, so you don’t have to be all that astute to be way ahead of the game. Decide what you need to build, and get to work.

EXIT is a fraternity dedicated to taking a short position in managerial systems, and building the human institutions that come next. Learn more at exitgroup.us.

EXIT News

Weekly Full Group Calls, Tuesdays at 9PM ET:

12/30: EXIT Year in Review — what we’ve accomplished in 2025, and what we will build in 2026.

1/6: The fifth anniversary of January 6th — what went wrong, and what can be learned.

1/13: Joshua Sheets from Radical Personal Finance, on community building, financial preparedness, etc.

1/20: Mikkel Thorup from Expat Money, on acquiring productive assets overseas.

1/27: Book Club with Johann Kurtz on his book, Leaving a Legacy.

Member meetups — Members can check their regional channel or contact DB for full details.

1/9: Nashville.

1/10: Houston.

1/10: St. Marys, KS.

1/16: Columbus.

1/19: Dallas.

1/21: Denver.

1/24: Austin.

1/31: New York City.

2/7: Washington, DC.

RSVP links for EXIT cocktail hours in Dallas (1/19), New York City (1/31) and Washington, DC (2/7) available below the paywall. EXIT cocktail hours are a great way to get to know your local EXIT guys and find out if full group membership is right for you.