The Chinese are doing everything right, and they're still going to lose

The Chinese have been on a generational bull run.

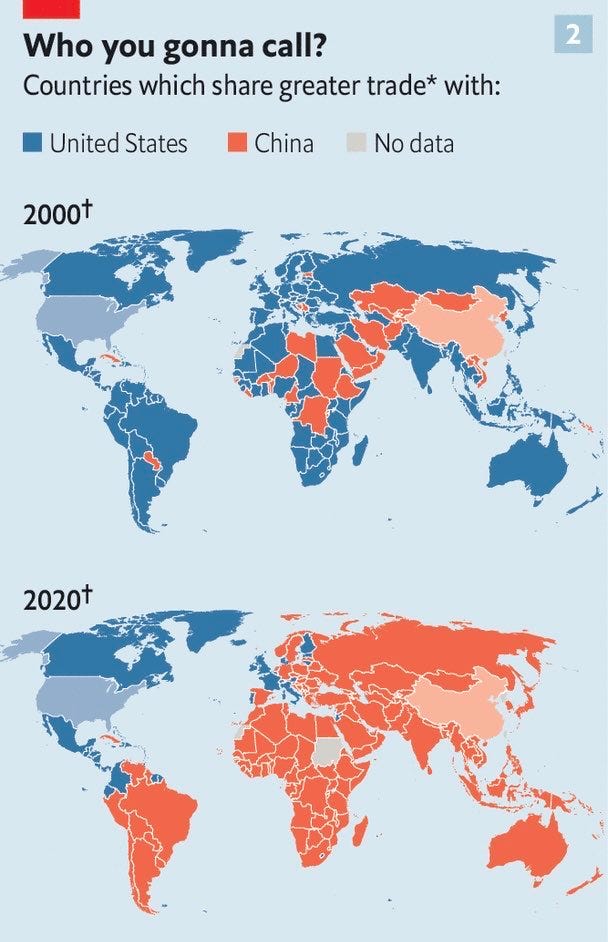

Like the Japanese, they spent thirty years clawing their way up from bottom-of-the-barrel low-cost, low-skill manufacturing, to become a genuine military, industrial, and technological challenger to the United States.

In fact, on the performance indicators that defined power in the 20th century, China already dwarfs the USA. Their standing army is roughly one-third larger. They produce nearly twice America’s overall manufacturing output, 10x our steel production, and 230x our shipbuilding capacity.

Of course, those indicators may not define success in the 21st century — but China has also reached parity or better in AI, robotics, and even the quintessentially American game of social media. They aren’t a low-tech, brute-force player anymore — they are approaching full-spectrum economic leadership.

Like America at the beginning of the 20th century, China has been peacefully expanding under the defensive umbrella of a declining naval and economic hegemon. Like the British Empire before it, America’s imperial commitments are becoming expensive and domestically unpopular, and China is openly preparing to take the wheel.

China is advancing on every front — except one.

According to Chinese government statistics, China’s population began declining in 2021, from a peak of 1.412 billion. Their workforce has been in decline since 2015.

This makes their situation massively different from America’s in 1914, because there are only two ways an economy can grow: through increased productivity per worker, or through natural increase (producing more workers.)

When a nation’s population is growing, they don’t just get more workers — they also get the natural stimulus of increased demand, as the growing, youthful workforce demands more homes, more electrical generation, more manufactured goods, expanded infrastructure, etc.

Conversely, when the population is declining, speculative and expansive investments become much more dangerous.

For instance, if you bought a house at the top of the inflated US real estate market in 2008, you could wait a few years for demand to catch up — but if you bought one of China’s 80 million vacant apartments, allegedly enough to house 3 billion people — those homes will never be occupied in your lifetime. They’ll literally rot and be reclaimed by nature first.

America has made empty promises to its retirees in the form of unfunded Social Security and Medicare entitlements — but China is performing a similar shell game in real estate.

China’s social programs for seniors are minimal, so workers must retire from their personal savings — but China severely restricts retail financial investing and capital outflows overseas, so most Chinese households’ primary investment vehicle is domestic real estate: 70% of Chinese household wealth is in their home(s), compared with 29% for US households.)

This is not equivalent to an “overheated” market that will crash and then recover: these investments are worth zero yuan, they will never be used by anyone. Building these fake projects “in the real world” with heavy machinery is arguably better than doing it with confabulated financial instruments (at least the machinery and labor training are theoretically good for something) — but the investments themselves are 100% fake.

And real estate is only an example of the larger phenomenon: capital markets depend on the promise of growth.

Investors will tolerate short-term volatility in the pursuit of long-term growth, but secular (long-term) stagnation breaks that implicit promise. Even a slow-growing economy can “correct” and refactor in ways that a shrinking economy cannot.

Seen through this lens, modern China’s 20th-century analogue is not the United States, but Japan.

Like Japan, China is a highly cohesive, high-IQ, well-educated, and increasingly highly-automated society.

Through the 1980s, Japan was eating America’s lunch in high tech manufacturing, running up a colossal trade surplus and buying up American real estate.

By 1995, Japan’s economy was ~72% the size of America’s, with a population less than half as large. They were making better decisions across the board — saving diligently, educating their children in STEM, investing in automation. And despite Western cope about East Asians as uncreative productivity machines, their cultural exports were (and are) increasingly popular and influential.

As a nation, Japan’s “play” was impeccable.

So what happened?

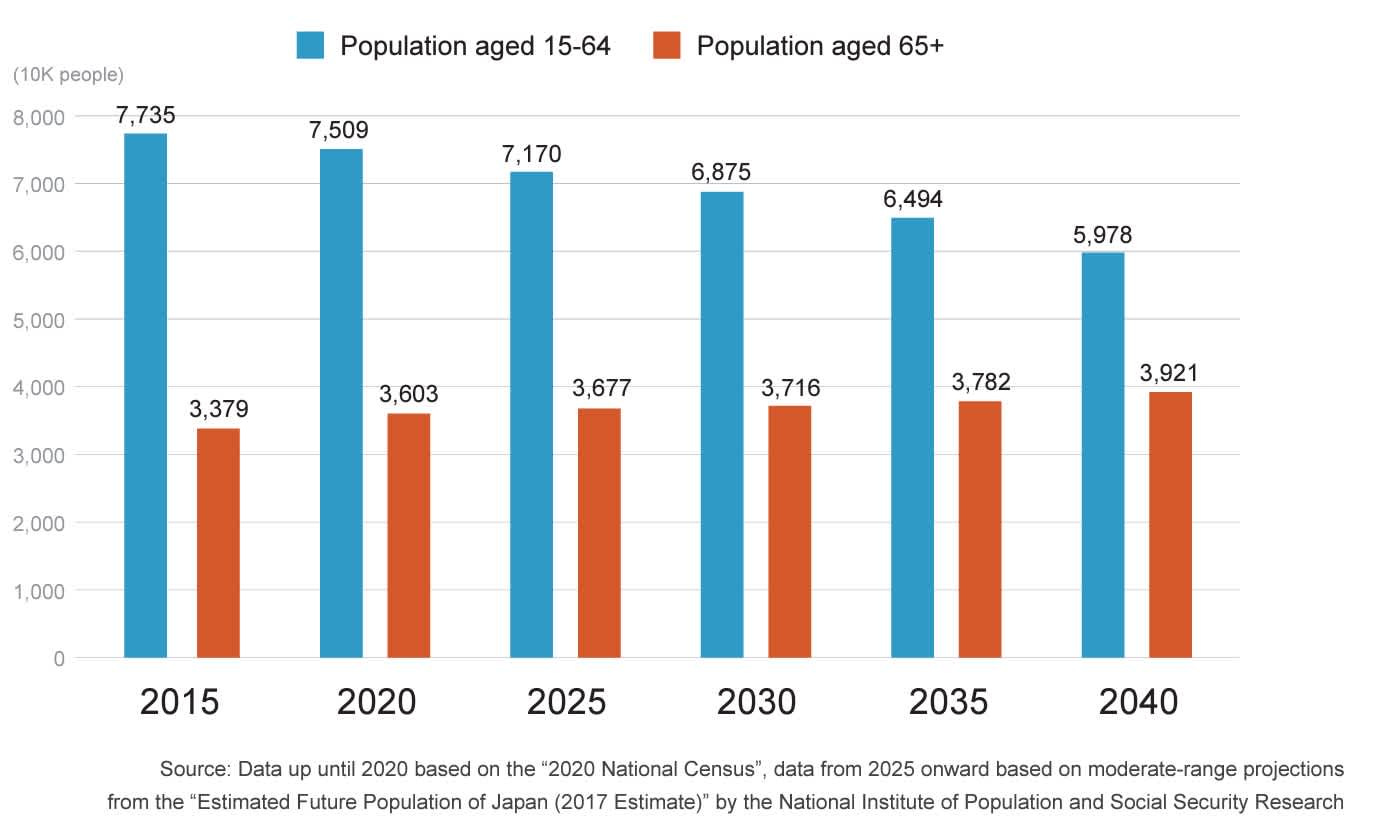

Basically, Japan got old.

Despite continuing to save diligently and invest in education and automation, their increased productivity per worker simply could not keep up with flagging demand, higher interest rates, and the growing financial burden of caring for the aged. Their gerontocratic corporate cultures continued to execute precisely and efficiently, but could not innovate.

And Japan’s demographic problems continue to accelerate: the ratio of dependents to workers is rising, and rising at an accelerating rate.

The anemic economy and clogged ranks of Japanese upper management place a drag on young Japanese workers’ prospects, which make them less interested in (and less capable of) family formation.

The problem of population collapse isn’t self-correcting: it gets worse as it gets worse.

And unlike Japan, China is getting old before it gets rich.

Despite the dizzying drone shows over Shenzhen’s cyberpunk waterfront, China’s GDP per capita is still only $12,600 — less than Malaysia, but more than Montenegro. They have a massive population that is aging in poverty, and whose primary retirement savings vehicle is obviously fraudulent.

Assuming that China’s demographic problem in the 2030s is no worse than Japan’s in the 2000s, China’s publicly reported growth rate in the mid-five-percent range will not be nearly enough to absorb their demographic headwinds — and that rate includes all the subsidized ghost towns that are going to zero.

It would take science-fiction, borderline-eschatological advances in automation and artificial intelligence for Chinese economic growth to outpace their demographic problem.

Essentially, the only way for the Chinese to “grow their way out” and escape a Japanese-style plateau is the mass deployment of all-purpose autonomous humanoid robots — which would simply introduce a different existential crisis for the Chinese state (and possibly all of humanity.)

And China is not the only nation facing this problem.

While the US population is technically growing, this is largely the result of immigration and immigrant fertility. Native-born American fertility is in decline, albeit on a more gradual course than the Chinese.

And even if you regard these populations as fungible economic units, the fertility of immigrant populations is collapsing, both in their own countries and (especially) in the Western countries to which they emigrate.

The problem cannot be solved with other people’s kids, even as a matter of naive arithmetic.

Ultimately, as a wise man once said: “No worldly success can compensate for failure in the home.”

Next month, in Austin Texas, We are assembling the world’s foremost experts in demography and fertility studies to find the root causes of demographic decline, and convert that knowledge into practical guidance for policymakers and families.

Demographic decline will be as significant in the 2030s as AI has been in the 2020s — there is no domain of human life that it will not touch.

And just like AI, the people who see the future coming will be ready to take the lead in their families, communities, and nations.

The conversation is happening March 28th and 29th, at NatalCon.

You should join us if:

You want to meet values-aligned individuals and families

You want to find solutions to the derangement of modern dating

You want to create good conditions for your children to have children

You want to protect your community’s reproductive and endocrine health

You want to find partners or investors for a natalist business or policy initiative

You want to preserve and grow wealth under conditions of demographic decline

Learn more at natalism.org, and use offer code NATALISM for 10% off your ticket.

EXIT News

On last week’s full group call (2/4) we had our Book Club on Neal Stephenson’s Diamond Age.

On this week’s call (2/11) we heard from Lomez on leadership through art and aesthetics. Recording available soon to paid subscribers.

On tomorrow’s Big Ideas call, we will discuss getting an SBA loan to buy an existing business, from an EXIT man who has secured a loan in the <$5M range.

Our Homeschool Call has begun with a UK EXIT man who has been a private instructor at several elite private schools in Europe. Great insights on the cultivation of disciplined creativity.

EXIT guy Tony is restarting the Scouting Call to continue developing our curriculum, based on Clay Martin’s “irregular ODA” concept. Members can check out the #scouting channel to learn more.

Houston members-only meetup was a success. Monthly Houston meetup schedule to follow soon.

EXIT now has a meeting space at Hightower Dallas, through our friends at New Founding. Big thanks to the D/FW EXIT crew for closing the deal. We’ll hold regular meetups there, in addition to using it as a coworking space. Dallas guys can check the #texas chat for more information.

Cocktail hour invites for Dallas (2/17), Salt Lake City (3/1), and Seattle (3/8) available to subscribers below the paywall. EXIT cocktail hours are a great way to get to know the EXIT guys in your area and see if the group is right for you.